He was a brilliant engineer, responsible for many civic works projects in Spokane and the construction of aerial mining trams in the Kootenays and around the world.

The company he founded lasted the better part of a century after adapting its technology to build chair lifts for ski hills.

But you’ve probably never heard of him.

Even if you’re familiar with the Riblet Tramway Co. you may associate it with Royal Riblet, who was happy to take credit for his brother Byron’s ingenuity.

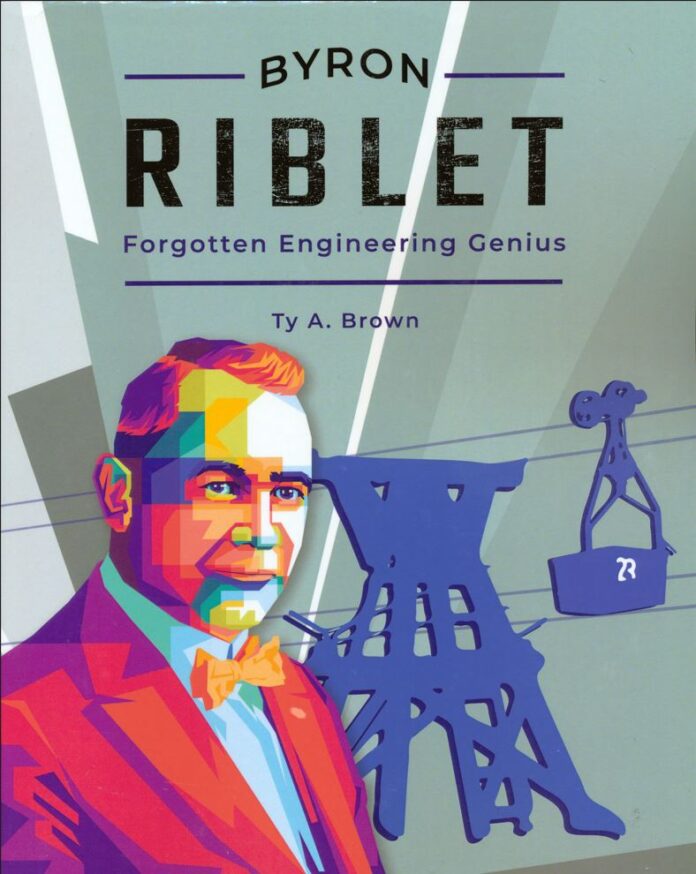

Now a Spokane author has published a book attempting to set the record straight and rescue Byron’s legacy.

“He did so many things in terms of not only engineering but developing Spokane and a company that was so successful,” says Ty Brown, a high school English and history teacher.

“It’s unfortunate the turn of events that left him forgotten for so many years. Hopefully this will bring to light this great man.”

A local history buff, Brown knew Byron’s home was somewhere on the Little Spokane River, in the same valley where he lives. In fact, it turned out be less than half a mile away.

That quest set him on a path that resulted in Byron Riblet: Forgotten Engineering Genius.

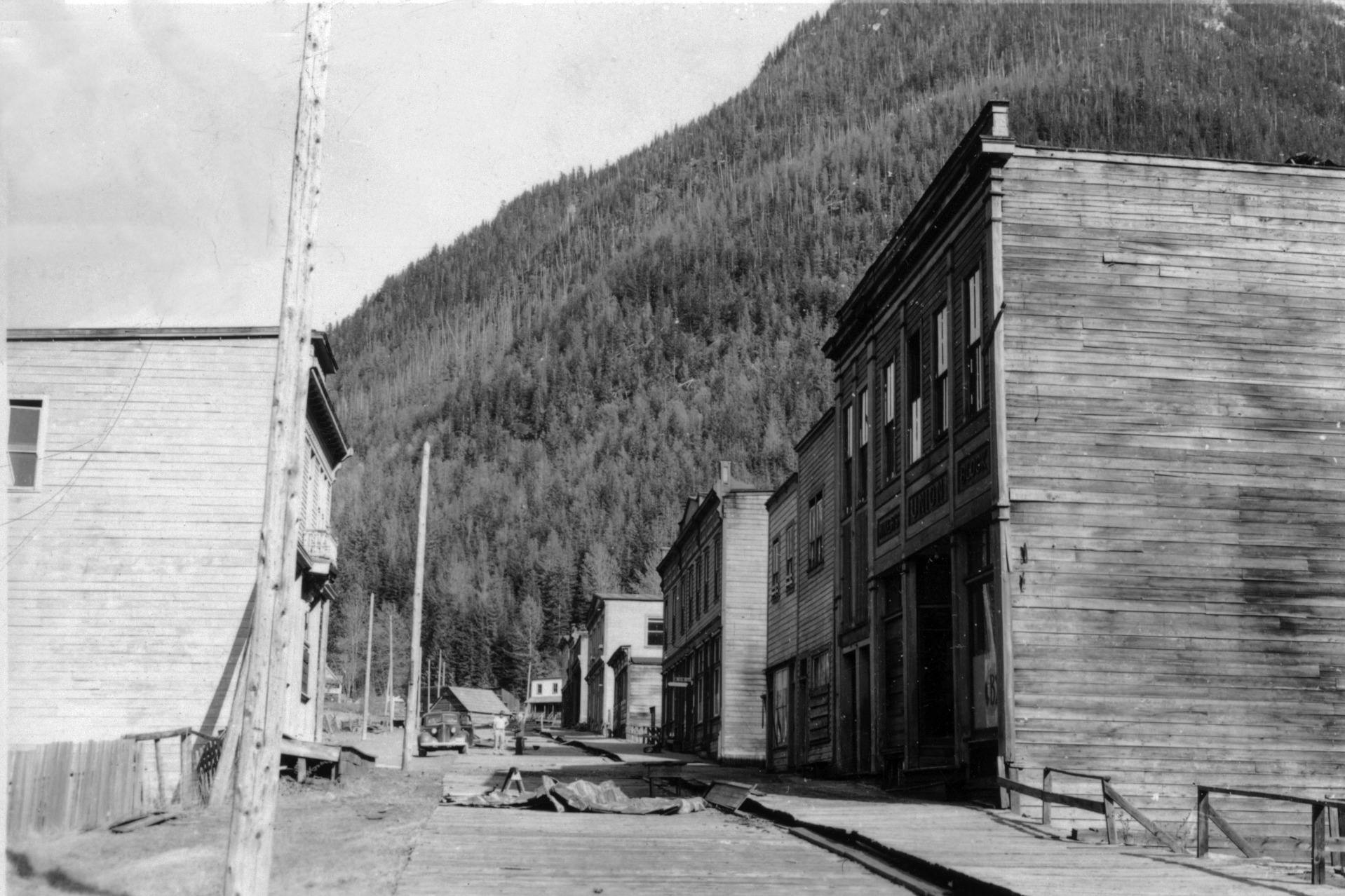

Legend has it Riblet’s claim to fame came about by accident. After several years as a civil engineer in Spokane, where he helped rebuild the city following a catastrophic fire in 1889, he was asked to come to Sandon to build a tram.

Only Riblet thought that meant a streetcar system. In fact, the job was to construct an aerial mining tram to bring ore down from the hillside.

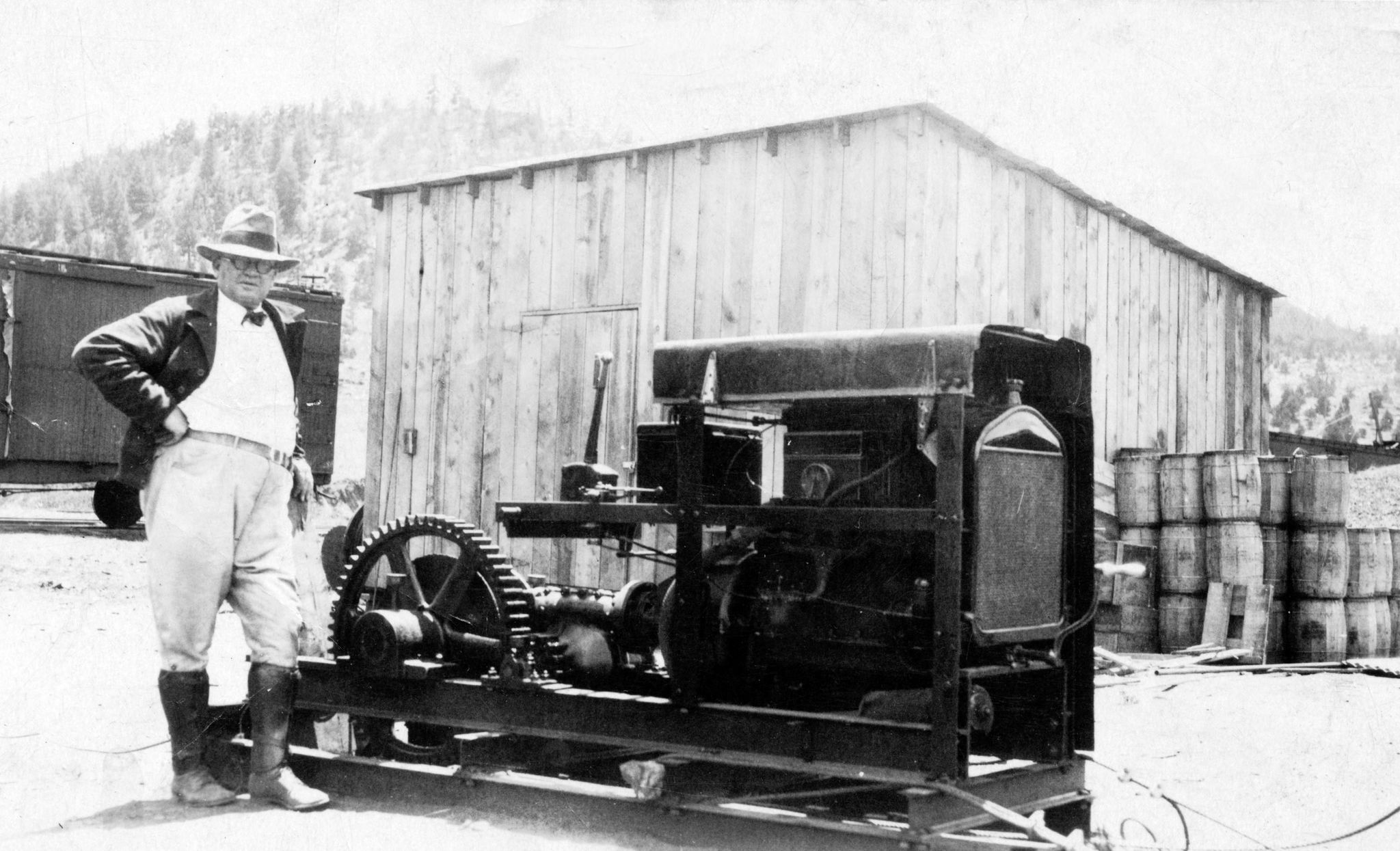

Riblet had no experience with those sorts of trams, but before long, his clever mind was thinking of ways to improve them.

“It was a good decision because it jump-started his career and the Riblet Tramway Co. ended up supplying aerial trams in the Kootenays and all over the world throughout the early 20th century,” Brown says.

The company maintained an office in Spokane and a factory on Lake Street in Nelson. Byron’s brother Royal came to Nelson to act as manager and salesman.

The Nelson operation flourished until about 1918, when the Riblets retrenched to Spokane. But business boomed in the 1920s, and Royal was given a 40 per cent interest in the company.

With his newfound wealth, he built a large home overlooking the Spokane River called Eagle’s Nest.

The Great Depression took a severe toll on the brothers’ finances. Byron also accused Royal of selling tramway equipment behind his back and pocketing the money for himself. Byron fired Royal in 1933 and thereafter the two reportedly never spoke again except through their lawyers.

That same year Byron’s home burned down.

But the company bounced back, building its first ski hill chairlift in Oregon in 1938 and going on to ever greater heights, literally and figuratively.

Royal, at least, retained his public stature. His home is now the Cliff House at Arbor Crest winery.

“So many people know about that home and refer to that as the Riblet home,” Brown says. “People just assume he must have developed the Riblet Tramway Co. and did all the engineering Byron did. The book corrects the history. No, Royal is not the one. Byron is.”

Byron died in 1952, not penniless, but having lost most of his wealth.

The Spokane Chronicle eulogized: “It is not often that a man is privileged to leave so many tangible and creditable monuments to his genius.”

Yet Byron fell into relative obscurity. His ashes, along with those of his wife and daughter, remained unclaimed for 70 years. Last year, Brown was part of a group that had them interred and a marker placed on the site.

Meanwhile, Chuck King, another Spokane historian interested in the tramway company’s history, was in touch its last president, Doug Sowder, who was selling the remaining assets.

Sowder granted them access to the company archives, including thousands of tramway photos. “They had a plethora of information in their basement,” Brown says. “Doug was gracious enough to give us that.”

What Brown originally envisioned as a magazine article grew into the book.

His research also brought him to Sandon and Touchstones Nelson. “[Byron] left a great mark in the Kootenays and other places in BC,” Brown says.

The book is available in Nelson at Otter Books and Touchstones.

You can listen to the full interview with Ty Brown here: