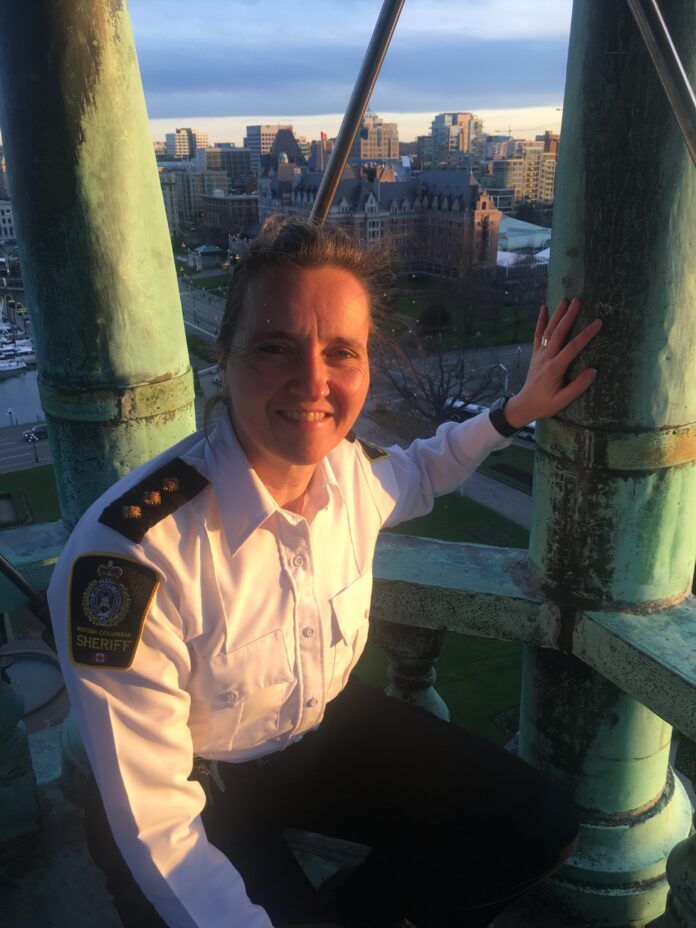

Iris Steffler recently retired from a lengthy career with the BC Sheriff Service that saw her become the first woman to serve as Sheriff of the County of Kootenay and the first to cover both the East and West Kootenay since the service was reorganized in 1974. Sheriffs handle courthouse security and prisoner transfers, among other tasks, but usually go about it quietly, so their important role is not always well recognized by the public. In an interview with Vista Radio, Steffler gave us a behind-the-scenes look.

When you told people you were a sheriff, did they understand what that means in BC?

To the very last day, the most common question was “What does the sheriff do?” My experience is that people equate the word with the American sheriff, which more closely mirrors police work.

I explain that the British Columbia Sheriff Service provides protection and security services to the court system. The police conduct investigations and sometimes effect an arrest. The sheriffs then take over transport of the accused person throughout the court process up to and including trial.

Most people don’t know what sheriffs do. We don’t speak to the media. We’re not out in the

community doing a lot of visual things, so people see us quietly drive down the road and wonder what the trucks are about.

When and how did you join the BC Sheriff Service?

I wasn’t looking for a career. I was just trying to figure out a way to pay the rent. I had gone to Selkirk College to take the legal secretary program and was hired March 3, 1986 as a court clerk. Sitting in courtrooms, watching sheriffs, getting to know them, intrigued me. I wanted to be a police officer just from exposure to what they did in court. Sheriffs was a precursor to that. So in the fall of 1988 I went to deputy sheriff training at the Justice Institute.

Back then they had female deputy sheriffs escort female and male prisoners. Male sheriffs couldn’t escort female prisoners. They were in the market for a female officer to fill that need. I later went over to the RCMP for a few years, then came back to the sheriffs.

What kind of changes did you see over your career?

The biggest change was our gear, training, and equipment. When I started they wanted me to wear a skirt. That was the end days of female officers wearing skirts. I pushed back. I didn’t want to wear one because I couldn’t see myself being equal to male officers or being able to run in a skirt. I was not required to wear one. It became optional at that point.

I was issued just a regular belt with a pair of handcuffs. Now we’re pretty much dressed like police officers with body armor and weapons and duty belts. With that comes all the training, from use of force to mental health awareness and de-escalation.

That was the biggest change, going from almost a matronly kind of position, with a skirt and big saddlebag purse, to being fully equipped and trained as a law enforcement officer. We have some similar training to police but we are not attending to calls in the middle of the night not knowing what we’re walking into. So from that perspective it’s a different job and lifestyle.

We certainly have our moments. I used to say “95 per cent of the time they pay me too much and five per cent you can’t pay me enough.” Our gear and training is similar, but the job is completely different from policing.

Did the job itself change? Were you doing different things when you started?

When I first started we executed orders for seizures of property to satisfy court judgments. I remember, for example, I did four seizures on one logging truck to satisfy a writ. We no longer do that. We used to serve a lot of divorce papers and litigation-type documents as well as evictions. Anything civil was privatized or reassigned to court bailiffs in the late 1980s, early ‘90s. We focus mostly on criminal courts and security within the courthouses.

We have seven main functions: court security, jail, escorts, juries, coroner’s juries, civil warrants, and criminal documents. Primarily the functions have remained the same. A few extra things have been added over the years including taking DNA samples when DNA data banks were legislated.

How did your career progress?

I left for three years to join the RCMP but decided I liked some of the things the sheriffs offered, like Monday to Friday work. I transferred back to the sheriffs. I had moved out east to Ontario and then came back, worked in Kelowna for four years as deputy sheriff, and then back to Nelson. A vacancy for sergeant, which was second-in-command, came up and applied for it. I won the position and arranged in-custody transports for the Kootenay for a number of years.

Then our sheriff retired and they reassigned me to that position as a staff sergeant. A few years later the branch reorganized and put the sheriff position back into Nelson and with the added responsibility of the East Kootenay as well. It was the first time the position of the Sheriff of the County of Kootenay covered both East and West Kootenay. I competed for that position and won it in 2012, with the rank of Inspector.

What stands out for you the most in your career?

Certainly some big trials. When DNA first came in, there was a trial in Nelson and I got to sit in the courtroom and listen to the expert teach the court about DNA. As a deputy sheriff, I heard a scientist explain how DNA works. It was fascinating. Same with pathologists or traffic analysts or any number of experts. It was a way of getting educated without sitting in a university lecture hall. I find court quite fascinating. A lot of it is repetitive, but whenever something new came in, I walked out thinking “Wow, they pay me for this?”

Also the relationships, or the interaction with people I may have dealt with early in my career and where they are now. Whether it’s somebody who has been a repeat offender and we’ve almost grown up together, there’s a respect or rapport just having known each other.

One person stands out in my mind who was active in environmental protests over the years. I got to know her quite well. Just before I left she stopped in and brought me her book. Over the years we’ve interacted through my job. It stands out to me in terms of having met people early on and seeing where their lives have gone. I’ve always appreciated when people have conviction in what they believe, whether it’s environmental or any number of social causes. To be able to follow that along has been meaningful.

I don’t know I would have garnered that if I’d been moving to different parts of BC. Being in one community, you get to know people and how their lives progress.

Are you unusual among sheriffs for having spent the bulk of your career in one place?

When I taught at the Justice Institute, I said to the recruits “you can make it a job or you can make it a career.” As I grew older, I realized that’s exactly what it was. I didn’t say it flippantly at the time, I just didn’t realize how deep those words really were.

In sheriffs, a lot of people join as a stepping stone to other law enforcement agencies. Much like other sheriffs, I went to the police. A certain number of people stay and a certain number leave for other agencies because the grass is greener, the pay is better, more diverse duties, more exciting, or whatever the case may be. Sometimes they come back to the sheriffs. So there is a fair amount of turnover.

From my own experience, people who come to a community for a lifestyle stay with the sheriffs for a career. The 9-to-5. No night shifts and more life-work balance with family. Other people will use it as a stepping stone or come to our community but not establish roots and move on. So it’s a split.

But you had to do a fair bit of travel, at least within the Kootenays and interior?

Yes. Flexibility is one of the biggest competencies required of a sheriff. You go to work on Monday morning and the next thing you know, you’re on your way to Kelowna with in-custodies. Or Vancouver. Or perhaps you’re packing your bags to fly to Edmonton or to Ontario to pick up accused persons in custody.

That was a big appeal to living in Nelson. It’s a beautiful city but it tends to get grey in the winter if the valley is socked in. So for me the travel was a perk. At the very least, driving to Grand Forks for court, you’re up in the mountains and into the sunshine. I don’t know if I would have stayed as long as I did if there was no travel involved.

We don’t have a lot of jury trials in our area. How many do you think you worked over the years?

Probably close to 50. Mostly in the Okanagan when I worked there. Early days we had to select jurors by taking the voters list and phone books, cross-referencing names and hand-writing jury summons, then mailing them out. So that was a big task. Jury trials generally require more sheriffs than the average trial. I was a jury manager in the Kootenay for most of my career.

What was the longest deliberation you recall?

Two and a half days. It was when I was sent to work a jury trial on Vancouver Island. It went to deliberation in the afternoon and over two nights and then a verdict was delivered the third day. From the trials I worked on, maybe a third deliberated overnight, the rest lasted a day.

We’ve had way less jury trials in recent years than in the early days. I don’t know what the strategy of electing judge and jury or judge alone is but we used to have several jury trials a year, and now maybe one per year in the West Kootenay.

What’s it been like working in old courthouses in our area? They’re beautiful but I imagine they present some challenges.

It’s both a privilege and a challenge. For the better part of my career I worked in the Nelson courthouse, which is like a castle. We have to mitigate the risks. Sometimes you need more officers to carry out a certain type of trial. I was responsible for 11 courthouses and each one represents its unique challenges and you have to work around that.

But it’s very much a privilege too. There’s a certain amount of majesty within the large old courtrooms and courthouses.

You took on the role of the unofficial historian of the Nelson courthouse.

Certainly, myself and a colleague are very passionate about the history of the building. So I’m protective of it and want to preserve the stories. If only the walls could talk.

Anything you’d like to add?

A number of years ago, an executive said, “If you don’t want to serve the public, don’t be a public servant.” I took that to heart. I’ve met people from all walks of life and witnessed the human condition. I became a mom halfway through my career, so sitting in family court impacted me differently afterward.

The best thing I ever did was leave Nelson to appreciate it. It’s a lovely little bubble and I love living here, but there would be no perspective if I hadn’t left for a few years.

In Vancouver, you might transport 50 prisoners five miles, but here we would transport five prisoners 500 miles. We live in our communities, whereas in the bigger centers you may work in one community and live elsewhere. I would always choose a small community, but having said that, I might do a bail hearing in the afternoon and after work run into the same people I’ve just released.

When people ask me what I am going to do in retirement, I respond with, “Something where I meet people on their good days,” as I’m keenly aware and respectful of knowing that I met many people on their difficult days, hoping that through my job I was able to make the experience of attending court a little less stressful.