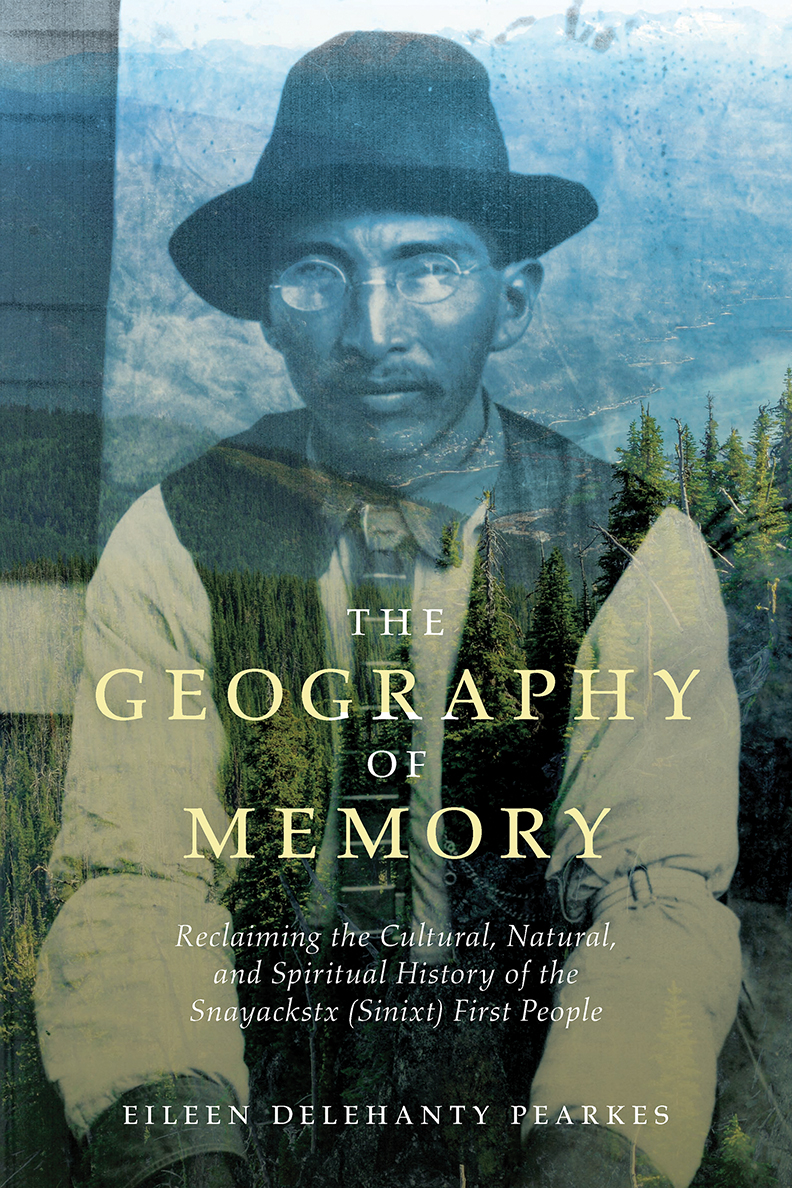

When Eileen Delehanty Pearkes’ book The Geography of Memory was published 20 years ago, it didn’t make much of a ripple, despite the importance of its subject: how the Sinixt people came to be alienated from their traditional territory in the West Kootenay.

“Its immediate impact was almost not measurable,” she says. “It was a very quiet book for a number of years. People’s interest in it spread by word of mouth more than anything. It had a more regional impact and even that was slow to build.”

It was not the first book about the Sinixt, but it was possibly the first intended for a general rather than an academic audience. Still, it arrived when where was little awareness or appreciation of the Sinixt among non-Indigenous people and few organizations formally recognized them.

Pearkes says the provincial and federal treaty processes only confused things, for Sinixt territory wasn’t included on the standard maps. That’s because the Sinixt, also known as the Lakes people, were declared extinct in Canada in 1956, although they continued to live in Washington state. In the late 1980s, they began to re-assert themselves in their traditional territory north of the border.

Two decades after her book came out, Pearkes says there has been a seismic cultural shift, helped in part by a Supreme Court of Canada decision last year that upheld the Sinixt’s constitutional right to hunt on their traditional territory in Canada.

That all set the stage for a revised and expanded edition of The Geography of Memory. Rocky Mountain Books approached Pearkes a few years ago about republishing the book, which is now a classic, but omits important developments that have occurred since 2002.

“All along the way the book supported their story, but eventually their story outgrew that first edition,” Pearkes says. “My recognition and understanding of the diversity of the tribe outgrew that first edition.”

Back then, she says she only had relationships with a few Sinixt people. But she has since discovered “what a diverse, talented, and amazing group of people it is.” Consequently, the new edition contains the voices of many contemporary Sinixt.

“It was a great pleasure for me to reach out to different individuals who have in their own work for their own people’s culture represented perspectives on the Sinixt,” she says. “There are lots of different voices in the book. That brings a rich dimension to it.”

They include Shawn Brigman, who writes about the sturgeon-nosed canoe and what he calls Sinixt placed-based architecture.

Dr. Laurie Arnold, who teaches at Gonzaga University, provided an essay about shifting politics and the Sinixt’s ability to be close to the international boundary.

Another contributor is LaRae Wiley, the director of the Salish School of Spokane, who has worked to preserve and promote their language and is descended from a man murdered near Revelstoke in the late 19th century.

Pearkes also added more maps to provide greater context and expanded on how contemporary perceptions of place are very different from the how the Sinixt viewed it.

“I’m quite passionate about the fact that we need to have a greater understanding of what things used to be like,” she says.

“Dams and railways and roads have altered how we see this landscape. In fact, prior to all of that built culture we had a very different kind of landscape that helps you understand how the Sinixt once inhabited it.”

Pearkes says when the first edition was published, she felt alone in her understanding of and willingness to broach the subject. Contrast that with an event at Lakeside Park in Nelson this past June, where hundreds of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people came together to celebrate last year’s high court ruling.

Pearkes says watching the Sinixt dance on the grass filled her with “disbelief and joy.”

“I never actually thought that was going to happen, and it did. This little book has followed along the whole process. We’ve come a long way as a culture in the past 20 years and I’m just thrilled for the Sinixt people, absolutely overjoyed for them that they are able to come home now.”

Listen to the entire interview with Eileen Delehanty Pearkes here: